As I progress through a course on learning analytics, I’ve been digging deeper into the relationship that librarians have with patron data, and I’ve determined that, like so many troubled relationships, it’s complicated. While the core value of patron confidentiality is now considered unquestioned and, indeed, inviolate, it is not as historic as some may believe. It was added to the ALA’s “Library Bill of Rights and Code of Ethics” in 1939, nine years after the initial release, at a time that is associated with the rise of Nazism and notable events of government surveillance (Witt 2017). While over 80 years old, this particular ethic has had some troubling beginnings and has taken some serious knocks from both external forces and from within the profession itself.

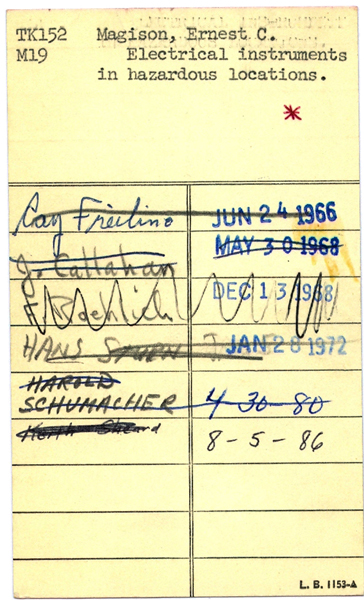

I also found the placement of this particular code interesting in the ALA Code of Ethics (current) – following customer service and intellectual freedom. Indeed, there are a number of ways that customer service has trumped privacy throughout the years. Consider circulation practices of yore, such as check-out cards with handwritten signatures of patrons who had borrowed each title, easily accessible to any person perusing the shelves. What would be the implications of borrowers of this title following an explosion in a lab if it appeared suspicious?

But I digress…my point is that customer service is the number one ethical obligation, but it is not meant to be at the expense of the other codes. Indeed, these other codes appear to constrain that #1 – guardrails, if you will. But to what extent should these constraints go?

The Prioritizing Privacy project, led by Lisa Hinchliffe and Kyle Jones, of which I have partaken, provides the opportunity for librarians to explore their own concepts and test their own assumptions about privacy and library services, particularly relating to learning and learning analytics. Taking a critical approach to both privacy and Big Data in academia (particularly higher education), the extended workshop brings together individuals at many points along the spectrum of beliefs and attitudes. Particularly intriguing to me were the discussions that brought out the disadvantages of libraries and librarians standing on the sidelines of this issue, not only for the institution of librarianship, but, most notably, for the students themselves, in the loss of services which could help them succeed in their own goals. But the key to ensuring ethical application of such services is the respect of students’ agency, an aspect that even the most ardent opponents of learning analytics can accept as a path to providing that “highest customer service” while still protecting the “patron’s right to privacy and confidentiality”.

I’m still exploring the privacy-analytics issue and have collected what I consider five foundational or key articles that explore the historical development and current struggles librarianship has with privacy (see References below). Witt, as I indicated earlier, provides a look a the intrigues, influences, and events which brought about the current ethos of patron confidentiality and privacy protection within the profession. Of particular note is Witt’s suggestion that the development of the codes of ethics in the 1930’s was less of a concern about the values of the profession and more about the development of librarianship as a profession itself (Witt, pg. 648). Regardless of the motivations, the codes were developed organically from statements in published literature and responses to surveys of ALA members, reflecting overall opinion of librarians, notably that reference transactions should be considered private and libraries should take steps to protect patrons’ privacy of information that they seek (ibid., 649).

Campbell & Cowan’s “Paradox of Privacy” focuses the privacy and service dilemma through the lens of LGBTQ (note: the authors specifically denote the “Q” as “Questioning”, which figures prominently in their discourse). They argue that the need for inquiry and the need for privacy are necessarily integrated, particularly for such a personal journey of the development of a young person’s identity. The title comes from the authors’ statement that, “open inquiry requires the protection of secrets” (Campbell & Cowan, pg. 496). After setting the context of this paradox, they argue for “the need for privacy” and the paradox of individual’s disclosure dilemma – disclosure can be risky and it can be healing. Indeed, the need for privacy within inquiry is imperative for the development of identity, but libraries have had mixed success in dealing with the competing needs of managing inventory with managing privacy. They describe how self-checkout systems have been shown to result in increases of use of LGBTQ material, contrasted with the increase of libraries collecting (or allowing to be collected by third-party systems) “big data” surveillance. Campbell & Cowan summarize Garret Keizer’s treatment and definition of privacy – “‘a creaturely resistance to being used against one’s will.'” – including providing Garret’s observations about privacy and libraries:

- Surveillance—monitoring what people are reading and sharing private information about them—becomes a form of using other people.

- Privacy consists of…individual’s power to modulate the extent of his or her self-revelation in specific circumstances.

- The library occupies a position of significant though paradoxical importance: its status as a public place makes it an ideal place in which to experience genuine privacy.

My takeaway from this slightly-below-surface-level look at libraries and privacy is that librarianship’s relationship with patron privacy is complicated. We value a patron’s right not only to access quality information on any and all subjects, but their right to keep this information private. However, we also value service and easy access to this information, and methods to improve these services can conflict with the value of privacy. But there are ways to reduce this conflict, mostly by returning control of information back to the patron. Transparency and honesty in how the information will be used, providing patrons access to their stored information, enabling patrons to opt-in and opt-out of these services, and simply letting go of the need to control information and resources are the solutions which I have discovered to have the greatest potential to ensuring trust in libraries is retained.

References

Asher, Andrew. “Risks, Benefits, and User Privacy: Evaluating the Ethics of Library Data.” Chap. 4.2 In Protecting Patron Privacy: A Lita Guide: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017.

Campbell, D. Grant, and Scott R. Cowan. “The Paradox of Privacy: Revisiting a Core Library Value in an Age of Big Data and Linked Data.” Library Trends 64, no. 3 (2016): 492-511. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0006.

Jones, Kyle M. L., and Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe. “New Methods, New Needs: Preparing Academic Library Practitioners to Address Ethical Issues Associated with Learning Analytics.” Paper presented at the The Annual Meeting of the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE), 2020.

Witt, Steve. “The Evolution of Privacy within the American Library Association, 1906-2002.” Library Trends 65, no. 4 (2017): 639-57. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2017.0022.

Zimmer, Michael, and Bonnie Tijerina. “Foundations of Privacy in Libraries.” Chap. 2 in Protecting Patron Privacy: A Lita Guide, edited by Bobbi Newman and Bonnie Tijerina: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017.

In addition to the usual suspects of such a meeting (“published” and “journal”), you might have noticed “Communism”. This is the result of a last-minute addition to the program: a presentation from

In addition to the usual suspects of such a meeting (“published” and “journal”), you might have noticed “Communism”. This is the result of a last-minute addition to the program: a presentation from

Specifically, “Faculty” and “Textbook” and “Student”. This is the effect of the emphasis on OER’s. The workshop was scheduled due in no small part to the number of proposals submitted on this topic. So it reflects true growing interest in the community.

Specifically, “Faculty” and “Textbook” and “Student”. This is the effect of the emphasis on OER’s. The workshop was scheduled due in no small part to the number of proposals submitted on this topic. So it reflects true growing interest in the community.